And now to explain the Flight Controller (FC) computer, here’s

the first guest post on this blog featuring James, the mastermind behind the FC.

James is a friend from high school who now lives in Austin and has joined the

HAPP campaign during the past several months as we attempt to bring this

project to fruition. James is also a “real” software developer, not a pretender

like me, and not only has he expanded what I thought possible on this project, he’s

also accelerated the whole project significantly.

I'll let James take it from here!

==============================

In the last HAPP blog update, Chris provided details about

the Autopilot (AP). This post will provide some background on the Flight

Controller (FC), the companion computer onboard the craft.

To recap from the system architecture overview, the FC is responsible for several key functions:

- Determining GPS coordinates, altitude, speed (horizontal and vertical), and heading

- Transmit GPS data plus other flight data of interest to the ground via satellite

- Receive ground commands, if needed, via satellite (normally the HAPP is autonomous)

- Process all flight data and commands and decide what actions to take, such as firing pyros to cut the umbilical with the balloon or pyros to deploy the parachutes

- Monitor the AP status and abort the mission if the AP stops responding normally (recall that the AP is listening similarly to the FC and can also terminate the mission independently if needed)

Electronics:

Like the AP, the FC is an Arduino Mega with two custom shields. There

were more than a few revisions prior to the delivery of final product for the

launch. My professional background resides entirely in the software realm. I’ve

written C-based firmware for embedded devices but I’ve never done much of the

electronics work myself. This project was a great bit of fun and provided me a

chance to stock up a full lab of gear (a desoldering gun is essential) and

components for future projects as well.

I began with the usual breadboard prototype, then moved it

to a more solid structure (protoboard) that required some light soldering. During

this breadboarding phase, I worked out the beginnings of the FC Arduino Sketch

that would serve as the scaffolding for the FC logic. I also mocked up a dummy

AP Sketch that did nothing but communicate on the I2C bus. You could type in state transitions manually

and see the status codes flow to the FC. Once satisfied that I understood how

each peripheral would work, I spent a considerable amount of time on electronics

revisions. Each involved multiple SKUs of the same component from manufacturers.

Some with built-in antenna, some without. Some with different form factors,

others with different voltage requirements. We finally settled on the smallest

available of each component that would suit our needs.

- GPS: u-blox MAX-M8Q

- Satellite: RockBLOCK 9603; uses the Iridium satellite constellation

- microSD: Adafruit MicroSD breakout

- Antennae: External Helical w/SMA (Satellite), Active PatchAntenna w/SMA (GPS)

The first unit is still in use and is my go-to development

unit here in Austin. It features built-in antennae for GPS and satellite

communications and is very portable, which is good when you have to sit outdoors

to test satellite communication. The craft-ready revision has small coaxial connectors

(SMA) for external antennae. Those antennae sit on the upper ELS deck, which is exposed to the sky, thereby avoiding the Faraday cage effect caused by the carbon fiber shell of

the craft.

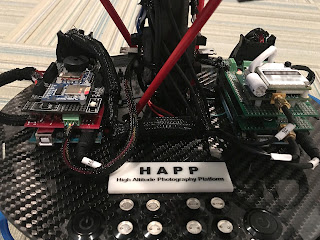

|

| Unit #2 installed on the HAPP as flight hardware |

|

| Autopilot (AP) on the left and Flight Controller (FC) on the right, as installed on the Electronics Deck |

The electronics of the FC are much simpler when compared to

the AP. We have a single I2C device to

communicate with – the AP. We have two

serial devices (GPS, Satellite) and a single SPI device (microSD). The Arduino Mega is equipped with four serial

ports, three of which are available via the Arduino header pins where we have

access to the transmit (TX) and receive (RX) pins of each (the first serial

port is accessible through the onboard USB connector and is used to program the

Arduino and serves as a debug port).

Future electronics enhancements might include the addition of

another temperature sensor for redundancy (the AP has one) as well as a traditional

GSM cellular communication channel for more frequent and higher volumes of data

while the craft is at low altitude. This could aid in recovery efforts should

we lose satellite communication. Chris

added this commercial, off-the-shelf tracking device from SPOT as a backup in the meantime.

Software:

The FC sketch has an initialization phase where it confirms

that the peripherals are in working order. It opens two log files on the

microSD card, one for general log data and another for CSV-formatted GPS data

for later viewing in a tool of your choice.

Once setup succeeds and the FC reaches a state called PRELAUNCH_AWAIT_FCAP_HANDSHAKE,

we await communication with the AP before handing off flight control to the FC

logic.

The main microcontroller loop of the FC code services the GPS

peripheral. For simplicity, we chose to stick with a serial interface for our

chosen chip, the MAX-M8Q from u-blox. I found a high-altitude capable variant

mounted to a breakout board by Uputronics out of the UK. Note that most civilian receivers will cease functioning around 18,000 meters / 60,000 feet. To track the HAPP up to 30,000 meters / 100,000 feet, selection of the right GPS receiver is critical.

GPS chips are constantly sending data to the communication bus. If you don’t devote time to servicing that stream of data, you risk losing characters and your GPS location fixes are in jeopardy. The cadence of the fix message is approximately one per second – more than enough for our positioning needs as GPS data is not involved in any kind of real-time steering of the craft. There is another class of GPS chips that provides higher accuracy and higher fix frequency. Coupled with predictive algorithms, that’s what your Tesla or military drones use for navigational guidance.

GPS chips are constantly sending data to the communication bus. If you don’t devote time to servicing that stream of data, you risk losing characters and your GPS location fixes are in jeopardy. The cadence of the fix message is approximately one per second – more than enough for our positioning needs as GPS data is not involved in any kind of real-time steering of the craft. There is another class of GPS chips that provides higher accuracy and higher fix frequency. Coupled with predictive algorithms, that’s what your Tesla or military drones use for navigational guidance.

While GPS fixes are being assembled, the FC sketch yields

time to a common worker function. It is

in that worker function where the FC does its work. That outline is:

- Ask the AP for its state

- Sync onboard clock with GPS satellite time

- Log positional and operational data

- Evaluate states for flight control logic (the secret sauce)

- Repeat ...

Chris wrote logic that reacts to the navigational input from

the fix data. He reacts to flight data

related to positioning, velocity and heading. He can respond to questions like

- Are we well outside of the bounds of the expected flight plan? Yes? ABORT! (There is a good story here from the first flight test. I’ll let Chris post about that later...)

- Are we descending unexpectedly? Yes? ABORT!

- Did we go supersonic on descent? Yes? Cool! Tell us about it.

- Did we lose contact with the AP? Yes? ABORT!

- More …

I should note here that the FC has multiple digital output

pins available via a header soldered to top Arduino shield. This is similar to an identical one on the

AP. The redundant pins allow either the

AP or the FC to issue critical abort control messages to the craft – fire the

pyros to cute down the balloon, release the chutes, etc.

Our satellite modem is able to send messages approximately

every 30 seconds. So, while we are

constantly collecting flight data, we can only send data to our application

server twice per minute. Once the FC logic detects that it is time to tell the

ground (that’s us!) about the craft’s current state, it assembles a formatted

payload and hands it off to the modem where some internal retry logic then

attempts to acquire a satellite signal and send the data. These messages are

called Mobile Originated messages (MO). It is also at this point where the

modem can tell the craft about any pending commands sent from the ground. These

are called mobile terminated (MT) messages. At present, we only issue a single

command which tells the craft to enter the EXECUTE_ABORT state immediately –

think BIG RED BUTTON. We did, however,

design it to be a general-purpose command control feature where we can set the

AP or the FC to any state desired.

While the satellite modem is attempting to communicate, it

hogs the microcontroller’s time awaiting a response. That is bad because we

need to service the incoming GPS data and we need to service our own

operational flight logic. To solve that, the library we use to talk to the

modem allows us to provide a callback function so that it can yield time back

to us. It is the same exact function that our GPS loop uses to process normal

flight data. So now we have two entry points

into that single function – our GPS working loop and the callback from the

satellite library. That can be bad. Such

code is said to be re-entrant since there are multiple processes or process

threads accessing the function at the same time. It doesn’t have to be bad, but

our satellite library allocates memory in such a way that we’d be clobbering

variables set by the other callers. To solve that, our sketch uses a semaphore

to gate access to the non-reentrant parts of the library.

During nominal operation, the FC will remain busy getting a

GPS fix, providing navigation data to the flight logic handler, logging data to

the microSD, sending data to ground control, and receiving messages from

ground. It does this in a tight, highly-optimized loop from mission start to

finish.

In an upcoming post, I will detail the software we call the

HAPP application server. We have servers

in the cloud (because of course) where we coordinate all of the messages and

present data logically (missions, messages, craft, etc.) for ground crew and observers. It has a web site as well as an API for use

by a dedicated mobile application currently in development by some amazing volunteers at Menlo Innovations in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

No comments:

Post a Comment